Abstract

The full title of this section is: Learning Values – The roots.

Section one introduces the ‘roots to shoots’ tree metaphor to represent my approach to inclusive learning design. The focus of the section is on values which support inclusive learning design represented by the roots of the tree. The word ‘inclusive’ is used as an acronym for 9 further inclusivity values that should drive the learning design process at every stage:

I. Intentionally equitable

N. Nurturing

C. Co-created

L. Liberated

U. User-friendly

S. Socially responsible

I. Integrative

V. Values-based

E. Ecological

For each root there is a ‘stimulus’ in the form of a contributed short text from a variety of colleagues from various continents, in the printed/ebook edition.

Co-creation chapter

Section one ends with a chapter about the ‘C’ root-value: co-created. It discusses partnerships in learning and teaching, in particular with students. It is about creating a collaborative, reciprocal process whereby various aspects of teaching, learning and research are developed with students.

This chapter has three case studies which explore very different aspects of pedagogical partnerships: (1) students as co-creators; (2) student partnerships in research; and (3) culturally respectful partnerships.

1. In the printed/ebook edition: The first case study, from the UK is entitled ‘Including the ‘Students’ as Co-Creators’ and is by Kiu Sum, a student. She writes about her first-hand experience of participating in a student partnership programme with a variety of co-creation initiatives she has shared in, highlighting what benefits she has clearly reaped.

2. In the printed/ebook edition: The second case study, from Canada, is about ‘Students as research partners’ written by Alice Kim in collaboration with her student Cassandra Stevenson. They discuss the four phases of partnership. Watch the authors discuss the implication for practice of designing research partnerships with students.

3. Here below: The third case study by Yifei Liang and Kelly Matthews (Australia) is entitled ‘Culturally respectful pedagogical partnership (Asia)’. Rather than a practice case study, this is a more conceptual piece where the authors, following a scoping review, explore factors which foster more culturally respectful partnership practices. The narrative sheds light on a number of important considerations when it comes to setting up intercultural student partnerships: ‘learners and teachers engage in ongoing negotiations of power and cultural identity in cross-cultural partnerships’ (Zhang et al. 2022). What platforms, language and activities are used set the tone for power relationships and, if done respectfully, can enhance intercultural learning for all involved. Watch a short video of the authors talking about the implications for practice of adopting a culturally respectful stance to partnerships.

Reference: Zhang, M., Matthews , K. and Liu, S. (2022). Recognising Cultural Capital through Shared Meaning-Making in Cross-cultural Partnership Practices. International Journal for Students As Partners, 6(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v6i1.4893

Culturally respectful pedagogical partnership (Asia)

By Yifei Liang and Kelly Matthews (Australia)

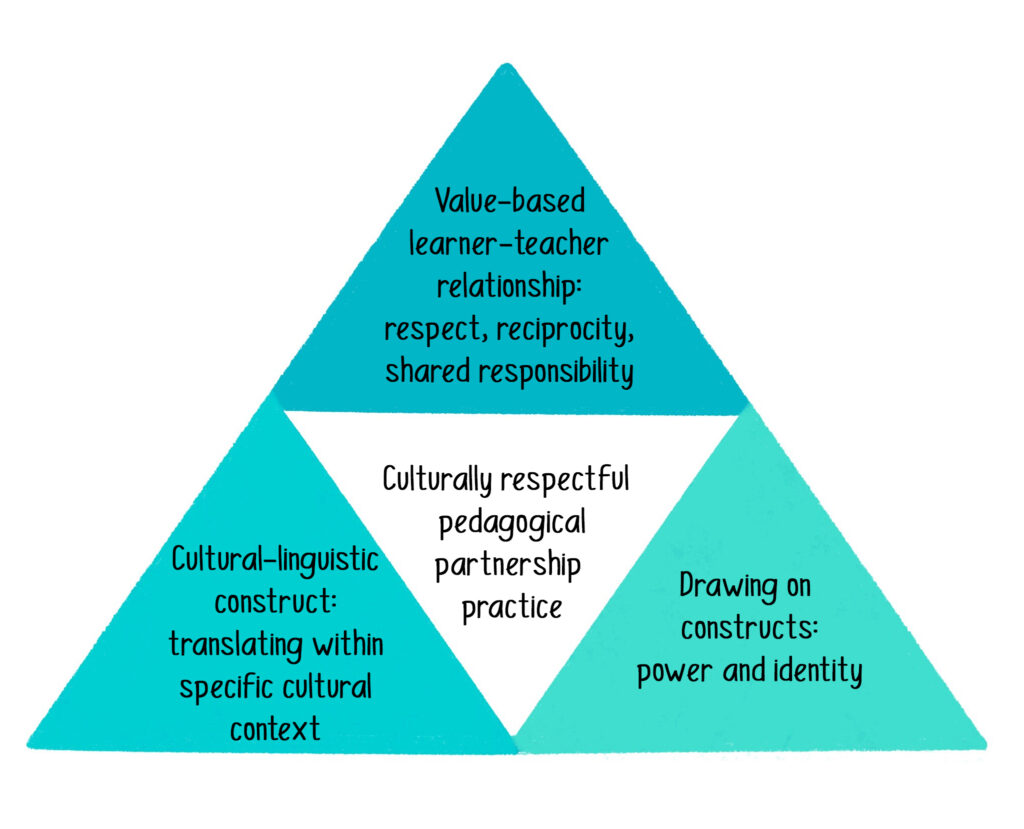

Students as Partners (SaP) is gaining increased attention in higher education. Rooted in a values-based learner-teacher relationship, SaP emphasises respect, reciprocity and shared responsibility in such interactions (Cook-Sather et al 2014). Engaging students as partners (e.g. co-creators, co-researchers, co-learners) in learning, teaching and research reshapes the traditional identities and power arrangement between teachers and learners (Matthews et al 2018). Although pedagogical partnership practices are implemented in many universities from diverse cultural contexts, our recent scoping review found that practices in Asian universities tended to transplant western practices and models of SaP (Liang and Matthews 2020). In doing so, the cultural norms and values in Asian universities emerged as troublesome and problematic when viewed through the western lens of SaP. Adopting an expansive view of SaP, what Healey, Flint, and Harrington (2014) called a ‘way of doing things’, means SaP is no longer a practice to be transplanted from West to East. Rather, it becomes a process of ‘translation’. Translating the mindset and ethos of partnership values within specific cultural contexts that can engender culturally-situated, and thus culturally respectful, practices and approaches; a creative array of possibilities where SaP both shapes and is shaped by the cultural contexts of the people involved. In this expansive view, SaP is a dynamic and evolving ‘cultural-linguistic construct’ that can deepen inclusivity (Cook-Sather et al 2018, Green 2019), as shown in the image below.

The tendency to transplant western practices to Asian universities, as evidenced in our scoping review (current SaP researches in Asia were mainly conducted in China, Singapore and Malaysia), meant that Confucianism as an all-encompassing value system was identified as a barrier to growth and implementation of pedagogical partnership in the implementing Asian countries. The spirit of respecting cultures, we believe, involves a criticality that questions blanket stereotyping of Confucianism and its impact on how learners and teachers will interact. Although Confucianism is entangled with a political ideology of control and hierarchy in modern times, the original foundations of Confucianism emphasise self-cultivation and social harmony that have been guiding people living in Confucian societies for centuries. Whether SaP is being implemented in Asian universities or with students from Asia studying in western universities, culturally respectful pedagogical partnership means calling into question our assumptions about culture, like Confucianism.

Image: The keys to explore culturally respectful pedagogical partnership

We need to clarify here that Confucianism is only one of the influential traditional cultures in Asia. To adapt SaP to diverse Asian cultures, we provide three steps to guide the implementation of SaP practices. Step one, as a precondition of cultural respect, is to understand the views and opinions of Asian students. Step two is to co-create practices and processes of partnership that are enriched through cross-cultural genesis by following the values of respect, reciprocity and shared responsibility, rather than transplanting or imposing western-centric model. Step three involves ongoing dialogue. This step likely starts with teachers opening up a space for discussion with students about their views and beliefs about the roles of learners and teachers to reshape identities and power arrangement. In doing so, introducing the values and ethos of partnership offers opportunities to re-imagine and establish new ways of working that feel right to both students and teachers. For example, in order to enable Chinese international students to better connect with academics and obtain more effective learning support, Stanway and others (2019) involved Chinese international students in a Wechat (a popular Chinese social media platform)-based partnership innovation as student consultants in an Australian university.

In this pilot, in addition to better understanding the communication preferences of, and feasible support channels for, Chinese international students, the use of their own cultural and language assets by the Chinese student consultants also avoided the local cultural privilege of the partnership and the cultural assimilation of international students (Stanway et al 2019).

We encourage more efforts and attempts. Time and ongoing discussion will matter as it is a journey of learning and unlearning that challenges many cultural norms, both in Asia and elsewhere although in different ways, about the roles of students in higher education.

Watch a short video of the authors talking about the implications for practice of adopting a culturally respectful stance to partnerships.

References

Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C. and Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching, Josey-Bass, San Francisco.

Cook-Sather, A., Matthews, K.E., Ntem, A. and Leathwick, S. (2018). ‘What we are talking about when we talk about students as partners’, International Journal for Students as Partners, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1513/ijsap.v2i2.3790

Healey, M., Flint, A., Harrington, K. (2014). Engagement through partnership: Students as partners in learning and teaching in higher education. York, England: The Higher Education Academy.

Liang, Y. and Matthews, K.E. (2021). Students as partners practices and theorisations in Asia: A scoping review’. Higher Education Research & Development, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 552-566. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1773771

Matthews, K.E., Dwyer, A., Hine, L. and Turner, J. (2018). Conceptions of students as partners. Higher Education, vol. 76, pp. 957-971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0257-y

Green, W. (2019). Stretching the cultural-linguistic boundaries of “students as partners”. International Journal for Students as Partners, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 84-88. https://doi.org/10/15173/ijsap.v3i1.3791

Stanway, B.R., Cao, Y., Cannell, T. and Gu, Y. (2019). Tensions and rewards: Behind the scenes in a cross-cultural student-staff partnership. Journal of Studies in International Education, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 30-48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315318813199

Inclusivity note

Setting up culturally respectful partnerships implies that we are prepared to respect (and value) other ways of knowing and doing things. Teachers who have not travelled much, do not speak other languages and come from monocultural backgrounds could find it particularly challenging to expose themselves to other cultures. Being honest about our limitations and candid about our attempts can help students have empathy and feel less nervous themselves.

Careful planning of the technological tools we choose is key: rather than students having to adapt to our tools, we can choose the tools that are most familiar to them.

Watch a short video of the authors talking about the implications for practice of adopting a culturally respectful stance to partnerships.