Listen to this Educational Burrito podcast about how my approach came about.

Watch this MyFest 2023 presentation of my ‘roots to shoots’ approach.

Read more about the key concepts below.

Inclusion is an experiment in attending to the quality of difference

Erin Manning

In this narrative I address several key concepts and share some background to the writing of the book Inclusive Learning Design. First, I go back to the key terms ‘inclusive’, ‘learning’, ‘design’ and provide a fuller explanation of their meaning than I do in the Preface of the printed/ebook edition. Second, I discuss why this book is needed and why now. Third, I share why I am interested in inclusive learning design and how this links to my educational philosophy. Fourth, I explain my ‘show rather than tell’ approach to writing the book.

Activate your inner dialogue… How would you answer?

What does ‘inclusive learning design’ mean to you?

What questions do you hope to answer by interacting with the book and this companion website?

Inclusive Learning Design

In the preface, I suggested this broad definition of inclusive learning design:

Inclusive learning design is design that considers the full range of human diversity with its complexity. It is designing learning environments, experiences, activities, tasks, assessment and feedback with students’ voice and choice at its heart, so that students can grow academically, culturally and socially.

In this section, I attempt to further expand on that definition by focussing, in turn, on the key concepts: inclusive, learning, design.

Inclusive

Like many words that become fashionable in education, the word inclusive has become an educational buzz word suffering from ‘dereferentialisation’ or the loss of specific referents (Readings 1995). Additionally, here are five examples of incorrect or limiting understandings of the term inclusive:

First: inclusive as a superficial ‘feel good’ term – this is not accurate nor useful and lacks conceptual rigour (McArthur 2021). With the mushrooming of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) committees, initiatives and policies in most UK universities, and with the concern on ‘student satisfaction’ this superficial use of the term inclusivity is becoming more common. Inclusivity is more than making everyone feel good.

Second: inclusive as synonym with providing ‘access’ to education or equitable access. Inclusivity has been defined as accommodating the learning needs of various students in existing mainstream educational offer. In this case, inclusivity is used as a synonym of equality. Although accessibility remains a priority, nowadays inclusivity is about a ‘shift in pedagogical thinking from an approach that works for most learners existing alongside something “additional” or “different” for those (some) who experience difficulties, towards one that involves providing rich learning opportunities that are sufficiently made available for everyone, so that all learners are able to participate in classroom life’ (Florian and Black-Hawkins 2011). Inclusivity is more than access to education.

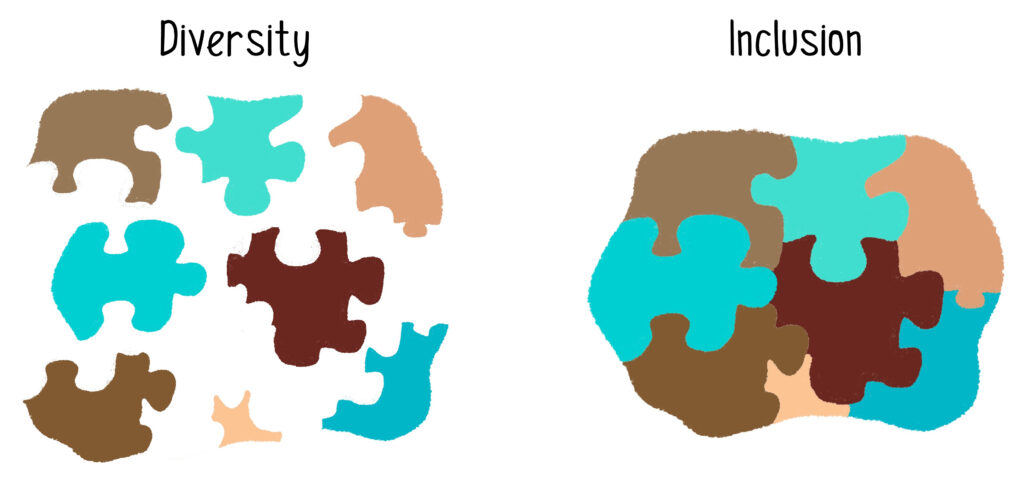

Third, inclusive as synonym with ‘diversity’. Students like being in diverse institutions but also where that diversity is acknowledged, welcomed and valued. You may have heard the saying: diversity is counting people, while inclusion is making people count. Diversity is a quantitative value, while inclusivity is the qualitative aspect. It’s not about how many people fit in which pre-determined categories, but how that diversity is used for the advantage of all. Inclusivity must be cultivated intentionally – not assumed to happen automatically just because diverse people are in the same space. Diversity can stigmatise, so it’s a fine balance: “students don’t want to stand out as different yet want to be recognised as individuals” (Hockings 2010). Consider this image to show the contrast between diversity and inclusion:

Image: Beyond diversity towards belonging

The image above is made up of two parts. The first part, to the left, represents diversity. It shows puzzle pieces which are diverse: different sizes, shapes, colours and position. They are all in the same space, but they do not form a unified whole because they are disjointed. In the second part, to the right, inclusion is represented by all the pieces joining to form an overall irregular shape where all the pieces connect to each other in a meaningful way. No piece is left out, no piece matters more than the others, each piece is an asset, has its place and is needed for the harmonious whole. Inclusivity is more than diversity. As my colleague Derek Yates said at an internal staff event: ‘Diversity is our reality. Inclusivity simply describes the most intelligent way to work within it.’

Fourth, inclusive as something to address ‘disadvantage’. The wording disadvantage is used by many with the good intention of highlighting that some have not had it so easy in life, for a variety of reasons. The issue is that it puts people into various ‘categories’ and makes them feel they have a deficit, they lack something and, ultimately the onus is on them to resolve the ‘disadvantaged’ position they are in. The UK Equality Act of 2010 recognised this issue by replacing ‘disadvantage’ with ‘discrimination’ which implies not a deficit but unfair treatment from the part of others. Yes, some students do have a disadvantage, but not because of any inherent fault or gap of their own, rather because the system puts them at a disadvantage by the lack of inclusivity it is premised upon. Inclusivity is more than addressing disadvantage.

Fifth, inclusive in the sense of ‘integrating’ students who are different and do not naturally fit in the system. This is about accommodating new perspectives in pre-existing rigid systems and help them ‘fit in’. This use is reminiscent of the word ‘integration’ which was used in the 60s and was later replaced by ‘inclusion’. This particular meaning is also the reason why many now reject the use of the word inclusivity – to them it implies that there’s a ‘container’ of teaching and learning (existing systems) and to be included means to become part of it by changing and adapting to fit in. Inclusivity is more than integration.

So, what is a better understanding of the word inclusive?

As mentioned in the Preface, inclusivity should be a habit of heart, a habit of mind and a habit of hand (Shulman 2005). Hence, it should be a value, a professional behaviour and a competence (Lawrence 2022). Good teaching is inclusive by default. Hockings (2010) defines inclusivity as: ‘the ways in which pedagogy, curricula and assessment are designed and delivered to engage students in learning that is meaningful, relevant and accessible to all. It embraces a view of the individual and individual difference as the source of diversity that can enrich the lives and learning of others’.

Inclusivity is above all about equity, justice and social respect. An inclusive approach to learning design makes us anticipate, acknowledge and remove barriers to engagement and success at university. It is about genuinely caring for each and every student and doing our utmost to support them in their learning by designing it in a way that caters for their learning as well as social and emotional needs.

Inclusivity helps us view students as whole beings who belong and allow them to truly shape their learning and their institution. Inclusivity asks of us teachers to let students ‘behind the scenes’: get them truly involved in the very learning design process and allowing them to shape the what, when, where and how of their learning (even within constraints), but especially the why. Owning the reason and purpose of their studies is highly motivational for students. Partnership with students, our ‘most important stakeholders’ (Austen et al 2021), is one of the most inclusive ways we can operate in higher education and I have dedicated a chapter to it at the end of Section 1 of the book.

Rather than a ‘technique’, inclusivity is more about the moral dimension of our role as educators. It is about becoming ‘attuned to difference for a justice-to-come’ (Bozalek 2022). Although inclusive teaching does not mean that you need to be an expert on every culture, health condition, religion etc., it points to a willingness to ask students, to engage in dialogue and make appropriate changes, and be eager to understand and seek out information/resources. Linked to this, extending a sense of care to students, as many institutions did during the pandemic, should be our default approach.

Rather than focussing on individuals, inclusion should be about improving the whole system, for everyone, on the lines of the ‘ubuntu’ African philosophy which highlights how all human beings are interconnected and interdependent. As Smith (2017) puts it: ‘Ubuntu precedes and goes far beyond Western, more instrumental, individualistic, and organizationally-contained, notions of inclusion. In an individualistic society, the goal is often self-centered: become individually healthier, earn a promotion, make more money, receive individual acclaim. In an Ubuntic society, the goal is always other-centered: promote the collective’s reputation, success, health, and sustainability’.

Inclusivity is about empowering students so they can see themselves as leaders of their own learning. Talking about traditionally underserved student groups, Jan MacArthur (2021) says that inclusivity is about ‘who those students are allowed to be and who they go on to become’. This matters because each one of us has a social identity and with it come some specific issues of power and authority. Some of us need to navigate dynamics that can hinder progress much earlier and much more often than others. Understanding how and why people are excluded is a fundamental first step in being able to address those barriers as inclusive pedagogy is about being ‘truly responsive to diverse groups of students’ (Hailu et al 2016).

This radical way of understanding inclusivity implies a paradigm shift: from inclusivity in the sense of ‘come join us and I will accommodate your needs so you can learn from us’ to ‘come join us so I can learn from you and together we can all create a new whole’. Clearly, what inclusivity means also depends on your context. For example, for teachers based in countries where there is an indigenous population (such as First Nations) with its own culture, inclusivity would foremost entail understanding, valuing and promoting indigenous knowledge systems. In most Global North countries, ethnic minorities (such as Roma, refugees, Black and more) have been traditionally underserved in education, so inclusivity very much means valuing the contribution that members of those minorities can make to the learning situation.

In the book I tackle inclusivity in all the dimensions of teaching and learning, with a particular emphasis on accessibility and cultural responsiveness.

Learning

To me, learning is not simply about the academic content of the discipline or field of study. In the preface, I defined learning as: the process of acquiring new understanding, knowledge, behaviours, skills, values, attitudes, and preferences. I believe that in the time students spend at university, their whole being is shaped by the experiences they encounter. Their attitudes, values and worldview are deeply affected by the formal and informal learning while they are with us. By the time they leave us they have ‘become’ someone else, not simply in terms of a new profession – they are now a nurse, a designer, a manager – but very literally as human beings, they are a new person.

In my discussion I will use: ‘learning design’ to refer to the broader process of designing a whole learning experience and environment; ‘curriculum design’ more when I discuss the content and assessment; and ‘course design’ more when the focus is on the design of university courses and modules.

A side note about the word pedagogy: andragogy, understood as the study and practice of adult learning, would be a better fit than pedagogy for the book. However, as pedagogy is a well-known term in education, I have opted for using it throughout, with the meaning of: the study and practice of teaching and learning.

An important question which has become high on the agendas of governments and funding bodies is: what is the purpose of university learning? We know for sure that students and parents/guardians (who both pay the fees…) are mostly interested in career progression and prospective future earnings, hence institutions tend to prioritise courses that provide a good career ladder. This is important, and of course we want our students to succeed in life, professionally speaking. However, this has turned many universities into factory-style ‘training’ centres where society are the customer and graduates are the end-product for the job market. We risk losing sense of the deeper purpose of a ‘higher’ education: universities should not only be educational providers that increase the agency of students by equipping them with greater academic and professional capabilities, they should also be guardians of critical thinking and inquiry and above all, they should contribute to the collective good. Through their studies with us, students should not only achieve personal ends, but also become ‘better’, well-rounded, human beings, to positively contribute to society, whatever they may be doing when they leave us. I discuss social responsibility in more detail in Section 1.

Bearing in mind this nobler purpose of university learning, what is the role of university teachers? I like that in Italian, the word ‘to teach’ is ‘insegnare’ which comes from the Latin ‘in’ + ‘segnare’ – literally to mark in, to leave a mark. This provides a good mental image of our role: we touch lives and leave a mark through the cumulative effect of the learning experiences and environments we design and orchestrate in our practice. We assist students as they become their future selves. Of course, much informal learning and social development happen outside of the university, but as we have very little control over those, my book is concerned with the design of the learning we do have control over, in the classroom. The book is about wanting to leave an ‘inclusivity legacy’ through the overt (intended) as well as the ‘hidden’ curriculum so that students can prepare themselves for their future lives. For that to happen inclusivity should be an institution-wide ethos and approach which permeates every aspect and every department of the university. But if that’s not the case (yet) at your institution, you can start by making a difference in your sphere of influence, in the design of the learning that your students experience.

What is the role of technology and media in learning (and teaching)? In the book, I have chosen not to have a separate section for ‘technology’ for teaching and learning per se, because I believe that the mode is not the most important consideration. The pedagogical principles, intentions and practices need to be clear and the mode of teaching and learning is part of the context analysis which I address in Section 2. The pandemic has accelerated many (overdue) technological advances and created new (human-)technological assemblages in teaching and learning where physical co-presence and digital learning are not mutually exclusive, rather they complement each other. The principles and practices discussed in my book apply to both modes and their various blends. Technology and pedagogy are deeply entangled and what matters is the leveraging of what the various tools for – and modes of – teaching and learning afford us and our students.

A word of caution: technologies are assemblages of tools and practices with their affordances and limitations – we can’t assume that all technology is inherently accessible and inclusive. Once more, this is part of the context analysis I propose in Section 2.

Design

Design is a creative act. It is the configuring of the various elements of a learning experience, their relationships and how to plan their ‘delivery’. All teachers are designers of learning to a certain extent because they are called to orchestrate a wide range of aspects of learning. Design must be experimental, not following a formula.

Design and planning are often used interchangeably, and although they often overlap, they are conceptually different. Design should come before planning. Design focuses on understanding where the ‘issue’ is and on finding a framework to address it. Planning is developing a course of action. In education, design is the thinking time we dedicate to understanding our course, its blueprint, its goals and learning thresholds, identifying creative approaches and configuring the various formative and summative assessment elements. While planning is more to do with putting together schemes of work and lesson plans on the basis of the design so that we can run the course.

The book is about interrogating what type of designer you are and how you can be a better, and a more inclusive designer of and for learning. This should be followed by careful planning, then by enactment (for instance running the course you designed and planned) and then evaluating the whole process to inform future (design) iterations.

Learning Design

It is worth spending a few words on the expression ‘learning design’. To be precise, this term was originally used mainly to refer to the configuration or purely online learning. Nowadays, it is a contested term and it is often used to mean curriculum design. Many agree that it embraces many things: it is an area of practice, a space for research, and a professional identity. Also, it refers both to the field of designing learning and to the learning design outputs.

Although there are now more models, frameworks and approaches to course/curriculum/learning design, these are not shared by all teachers: most of the learning design which goes under the umbrella of ‘preparation’, is usually unrecognised, a solo act, and hardly ever made public so it is difficult to reuse it. It’s as if, when it comes to learning design, we academics all speak different languages. The aim of Learning Design (capitalised when used as a field of study) is to provide teachers with an overall language and framework to describe teaching ideas in order to share them with other educators, in order to improve practice (Agostinho et al 2013, Conole 2013, Laurillard 2012).

A very important collaborative work on Learning Design is the ‘Larnaca Declaration on Learning Design’ which is a document arising from a meeting of Learning Design experts in Larnaca, Cyprus in September 2012. It uses the metaphor of music notation as a shared language for something abstract such as music to highlight that we can develop a system and language to share good teaching and learning. Learning Design is the effort to articulate the shared language of effective teaching.

The document states:

‘Learning Design is not a traditional pedagogical theory like, say, constructivism. Learning Design can be viewed as a layer of abstraction above traditional pedagogical theories in that it is trying to develop a general descriptive framework that could describe many different types of teaching and learning activities (which themselves may have been based on different underlying pedagogical theories).’ (Dalziel et al 2016)

The lack of a shared language for learning design coupled with the fact that university practitioners ‘do not share a common understanding of inclusive pedagogies’ (Stentiford and Koutsouris 2021) gets in the way of implementing inclusive learning design.

My book is an attempt to contribute to the establishment of a common language for Learning Design, using an inclusive lens to address values, context, content, assessment and evaluation.

A really important question in the context of this discussion is: can learning be designed? The reason this is a legitimate question is because one could argue that learning happens within, though it can be manifested outside, and you cannot design or force the neurological pathways in the students’ brains that happen as a result of learning. Indeed, we cannot force anyone to learn anything. What can we design then? What we can do as teachers is to provide the best environment, removing any potential barriers to learning, and designing learning experiences and journeys, for example through an interconnected series of meaningful learning activities, which support or prompt learning.

Goodyear and Dimitriadis (2013) suggest:

‘Design activity results in the creation of things which can influence behaviour, activity, experience and learning. (…) The most important kind of designed things (with respect to learning) are tasks: suggestions to the learner of good things to do. Learners’ activity can be strongly influenced, though rarely determined, by the tasks they are set.’

As context matters, here ‘good’ activities evidently mean valuable and relevant to the students and to learning situation at hand. In Sections 3 and 4 of the book, in particular, you will find many examples of learning tasks and how they can support more inclusive practices.

In view of the impossibility of designing learning as such, take the term ‘learning design’ used in the book as shorthand for ‘design for learning’.

Why my book is needed, why now (current HE context/priorities)

What are the main factors that have made a focus on inclusive learning design more necessary than ever before? To mention but the top ones:

Firstly, the increase of student numbers and types. The shifting demographics of our student body, with large amounts of ‘non-traditional’ students undertaking higher education courses; the perception of life-long learning as a universal human right; the need to cater for increasing seen and unseen ‘disabilities’, neurodiversities and learning needs; increasing numbers of mature and international students have all meant that the usual ‘on-size-fit-all’ offer is no longer adequate, if it ever was. Increased diversity presents us academics with opportunities as well as challenges: it can cause anxiety, tension and even conflict.

Second, legal requirements. In the UK there is legislation which supports inclusive practices such as the Equality Act of 2010 which prohibits discrimination in education and lists nine ‘protected characteristics’: age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation. The UK Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) Quality Code: B3 Learning and Teaching (2012) requires HEIs to provide inclusive learning through promoting equality, diversity and equal opportunity. All educational providers are expected to comply with these legal requirements, which can turn inclusivity into a tick box exercise.

Thirdly, remarkable global events. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement and the COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted inequalities and put a spotlight on underserved groups in society and in education which have resulted in a heightened interest in inclusive educational practices. For instance, access and accessibility to digital forms of education have been high on government and educational bodies’ agendas. There seems to be at present a renewed drive to address various types of disadvantages and many groups are willing to take action to address historical imbalances.

As a result of all the above factors, most universities nowadays have ‘Equality, Diversity and Inclusivity’ (EDI) policies and committees in place. This is a positive development if done well and with the right motives, such as to genuinely support students diverse learning needs. Unfortunately, these initiatives often result in lip service to the cause of inclusivity or simply as a public liability response. Besides, such initiatives rarely have a meaningful impact on the design of the learning experiences and environments educational providers offer, hence the learning students experience often remains unaffected.

We have a situation where there are major paradigm shifts in education which require a much greater emphasis to be put on inclusivity, so: why is inclusive learning design hard to achieve?

There are several reasons. Here are what I believe are the top ones:

Firstly, lack of first-hand experience: for most of us, our own experience of education was probably not very inclusive. This would have been painfully true if we belong to any underserved group, or to more than one – this is what originally Crenshaw (1991) named ‘intersectionality’. For instance, many colleagues have told me that they were labelled ‘slow and daft’ or worse at school, when years later it was found out they were simply dyslexics and the educational system did not identify or cater for their needs at all. The opposite can also be true: those educated in a mono-cultural environment, in ‘good’ schools that in various ways excluded anyone who was not the ‘norm’ at the time. As young students, we probably never even thought about issues of inclusivity or of privilege, just like fish do not know that they swim in water. But now we realise that our lived educational experiences have shaped how we feel about various groups and our ability to widen out. It is arguably much easier to implement inclusive design and practices when we have experienced them ourselves, but that is not the case for the majority who struggle to fully grasp realities that are alien to them.

Secondly, because inequalities in HE institutions and systems mirror the UK’s wider societal inequalities. We struggle to be completely inclusive because we live in a society where equity is not the daily reality for everyone, and this causes some of us to suffer injustice and all of us to develop deep-seated biases which become a mental barrier to develop more inclusive practices.

Thirdly, very few higher educational institutions have invested appropriate time, energy and resources in addressing inclusive learning design, even though they recognise there is a real need to improve things. Inclusive education does not just happen by itself, it takes effort, resources and skill. It is easier to design inclusive learning if we are afforded the cognitive space to do so and if there’s a whole departmental or, even better, institutional effort in this area. When inclusive learning design becomes a ‘solo act’ or we feel we are fighting for change against the grain most of the time, it becomes very tiring and wears us out emotionally and professionally.

This last point brings me to another important question: whose job is it to make the university a more inclusive place for learning? The short answer is: everyone, at every level, all the time. I believe we need a university-wide approach to inclusivity: from admissions to alumni; from the front-of-house to the classrooms; from beginner teachers to senior management; from facilities to library to catering; from policy to practice. However, a good place to start is you and I. Creating a more inclusive learning environment begins with you. My book is an opportunity to stand back and reflect on what a more inclusive learning design could look like in your context and how to embed inclusivity as a professional, pedagogical competence (Lawrence 2022), in your sphere of influence.

Inclusive learning design concerns university education from macro (programme) level to micro (individual lesson) level. However, the level at which inclusivity should take centre stage is the ‘meso’ level, at course and module level. Though institutional structures and practices vary, often there is a whole programme of study (say a 3 or 4-year degree), within it there are often sub-sections that can be called courses (such as a Year 2 course of studies or a subject within that degree programme), which in turn are made up of a few modules or units of study (some mandatory, some optional). To illustrate, the whole degree programme is like a whole book, the courses within it are the sections of the book, while the individual modules or units are the chapters. Some books do not have sections, just chapters; likewise some degree programmes do not have a subset of courses but are made up of a collection of modules or units. In the book, I am interested in learning design at the course and module level, rather than at whole (degree) programme level, because most academics do not have agency and control over the bigger programme level decisions and practices but operate at the ‘meso’ level of course or module. I will use ‘course’ and ‘module’ interchangeably to refer to the meso learning design level.

Because the course becomes the students’ ‘family’ space within the university, this is also where teachers tend to have more agency in terms of how they design and implement the learning experiences that make up the course. It’s at course level that teachers can embed inclusivity in a variety of ways and arguably have the biggest direct impact on students. The course takes life in the classroom (physical and digital). That space of actualisation of the curriculum provides a crucial space to put inclusivity in practice. As bell hooks (1994) put it: ‘the classroom remains the most radical space of possibility in the academy’.

For these reasons, my book focuses on inclusive learning design at course and module level, though you will find that most ideas and examples can be applied at lesson level and all the way up to whole programme level.

What is the result of inclusive learning design? Since the student experience is integral for learning and intellectual growth and has been shown to be correlated with academic achievement and retention (Austen et al 2021, Bornschlegl and Cashman, 2019, Sembiring, 2015), the aim is to create inclusive environments and learning journeys for students to grow, intellectually and socially. Academics intuitively know this, and they can see the imperative to support a wide variety of needs in their classes. Yet, they often do not know how to go about it. My book is my way of helping you as a teacher to interrogate your practice, to learn from colleagues who have successfully designed more inclusive learning and hopefully walk away from the reading not only with ideas to try, but more importantly a renewed hope that we can all become more inclusive in our learning design and practice.

My educational philosophy

The educational philosophy behind the book will become clearer to you as you read it, but here I would like to highlight my main pedagogical beliefs.

First, my philosophy aligns with a view of teaching as ‘a science, an art and a craft’ as Johnson (2017) puts it. Teaching is a science with its own body of research which teachers should consume and produce. It is also a science due to the ongoing experimental nature of teaching and informal data collection we engage with pretty much on a daily basis. It is an art because we are not standardised but unique, creative beings who constantly adopt and adapt various approaches to our context, just like an artist mixes colours and creates new effects with their palette. Our own teaching philosophy is in constant evolution. It is a craft because it requires a skillset learned through experience. (Johnson 2017).

The ideas and examples discussed in the book highlight the inclusive lens to scrutinize the science, art and craft of teaching.

Second, my philosophy aligns with what Baume and Scanlon (2018) sum up regarding the conditions that make learning most effective:

1. A clear structure, framework, scaffolding surrounds, supports and informs learning;

2. High standards are expected of learners, and are made explicit;

3. Learners acknowledge and use their prior learning and their particular approaches to learning;

4. Learning is an active process;

5. Learners spend lots of time on task, that is, doing relevant things and practising;

6. Learning is undertaken at least in part as a collaborative activity, both among students and between students and staff; and

7. Learners receive and use feedback on their work.

Third, my philosophy aligns with a socio-psychological perspective of learning, by looking at the interaction amongst the various elements that make up university learning. While looking at context, content, assessment and evaluation, I examine the interactions of teachers and students, the teaching methods used, the physical and digital spaces where learning is prompted, the psychological and emotional spaces. All these elements need to be understood in relation to each other and not in isolation. When we strive for inclusivity in all areas, we create a synergy.

Fourth, my philosophy calls for a ‘show rather than tell’ approach. I do this through the over 70 case studies in the book. Let me tell you more about them.

‘Show rather than tell’ approach

My book is not a theoretical work to advance inclusivity or Learning Design conceptualisation, but a practical guide. So, rather than spending much time finding the right words to define it or discussing the theory, I have briefly discussed the terms and concepts above, to leave space to showing you what inclusive learning design looks like in practice. I believe that the inclusive approaches, practices and examples discussed in the book provide a much better, broader picture of that inclusive learning design means than any definition could.

The main way in which I present these ideas to you is through practice case studies which constitute a selection of pedagogical ideas and resources, as a taster of the many inclusive pedagogical approaches at your disposal so you can choose appropriately in your practice and context. I chose to provide case studies because they are a form of storytelling, rich in context.

The case studies in the book (and on this website) provide a truly global kaleidoscopic view of learning design and are innovative in many respects.

Firstly, due to the way they are structured. You can see the author’s photo and read their bio; there is a short narrative (usually around 500 words, although some are longer); there are concrete references to support the practice with the research base; there is a visual aid (an image or a diagram); there is a box to highlight the inclusivity opportunities and challenges associated with each case study and there often are accompanying videos (where the authors themselves further expand on their narrative) on this companion website.

In this way, I am, by design, providing multiple means of engagement with the material, one of the main tenets of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) discussed in Section 1. Inclusivity is the golden thread and each case study is a nugget of inclusive practice. By reading the case studies in the book (and on this website), through the images that aid understanding, looking up the references that interest you most and watching the videos where the contributors say a little more about how to enact the inclusive learning design of their case study, you will come to ‘see’ what inclusive learning design looks like.

Secondly, because these are not simple anecdotes of inclusive practice but are examples of inclusive things done in practice to support students and remove barriers based on research. The case-studies contributors have identified the research base for their practice, so you can read about the practice in light of the literature. As teaching is perceived to be a heavily practice-based profession, many teachers lack an in-depth knowledge and understanding of learning theories. Research is often divorced from daily teaching practice as intuition and experience become the main influence on teachers. This practical guide attempts to bridge the gap between theory and practice, by presenting many different evidence-based case studies.

Thirdly, due to the remarkable variety of the contributors, in many respects. Contributors come from all the continents, with an equal split of gender. A good number come from the Global South (for want of a better term) and have various ethnicities, including People of Colour, Black or they belong to minorities in the country where they teach. They teach in many different contexts: mostly in UK universities; in universities in other countries; in FE colleges (UK); in community colleges (US); a few in Secondary and Primary schools. They belong to a wide variety of disciplines, from Maths to Psychology, from Nursing to Business. Their exact roles vary, but they are mostly academics. A few are known authors in the field of education and I am very honoured to include their respected voices in the mix.

Their contributions are mostly in the form of practice case-studies (cases in practice), but some are ‘stimulus’ (such as in Section 1) or a discussion of an inclusive learning design idea (a conceptual piece). Some are written in a more formal style, others are conversational. Mostly, the tone is that of a respectful professional conversation, so you can imagine these colleagues talking to you and telling you about their practice. The book embraces variety by avoiding a single voice (mine), consistent tone, or uniform approach. The chapters, and the contributed case studies promote and model a truly diverse approach to teaching and learning.

Fourthly, the overall effect they have on the book is that they not only point to inclusive learning design practices but contribute to redefine what inclusivity is really about. They constitute a form of research in the field of inclusivity: an alternative research type where practice is documented and interrogated (Healey et al 2020), embracing the students’ voice in contrast with dominant research paradigms and procedures. As you will notice most case studies refer or quote students’ feedback about the learning and some are written by students themselves.

The main reason for including so many different case-studies is to provoke professional cross-pollination for innovation.

Nearly all the contributors are university academics, but a small number come other sectors, including Secondary and even Primary school settings, because I believe in professional cross-pollination. Due to the siloed mentality we operate in, we are hardly aware of how things are done in other educational sectors. If you teach in higher education (HE), you may think that your professional development and networking should be tied only to your sector. You may be worried about ‘infantilizing’ higher education if you borrow pedagogical approaches from other sectors with younger students. However, with my book I am hopeful that you will come to appreciate the advantages of professional cross-pollination.

My whole educational career has been about cross-pollination as I have been fortunate to taste all educational sectors: Primary and Secondary school settings (both independent and state); Further Education (FE) colleges; Adult Education and outreach as well as 4 different UK universities. So, I have been fortunate to have experienced first-hand the ways of working, approaches and learning design in a wide variety of settings and sectors: I have borrowed some excellent practices from each sector and created my own higher education version learning design to suit my context.

An example of very successful cross-pollination from a non-educational field is the approach taken by Gareth Southgate as coach of the England football team which nearly won Euro 2020. Educators can learn an important lesson from Mr Southgate’s approach: he understood that he had better chances of success if he surrounded himself of highly skilled professionals from fields other than football, to avoid the risk of the ‘echo chamber’, where everyone thinks the same (BBC News 2021). A BBC News article on this commented:

‘The key is to bring people together whose perspectives are both relevant to the problem, and which are also different from each other. This maximises both ‘depth’ and ‘range’ of knowledge – leading to ‘collective intelligence’’ (BBC News 2021).

The takeaway for university teachers is: step out of your silo, expose yourself to pedagogical ideas from various sectors; see what works there and think about how you could adopt and adapt the approach to your context. In an age of ‘supercomplexity’ (Barnett 2020), it makes sense to learn from many different others. This example of cross-pollination can also be used to make a business case for inclusivity.

Cross-pollination is also intended in the sense that you may discover new connections between various approaches suggested in the book and come up with new inclusivity ideas based on the ones presented and thus become a pollinator yourself. Central to this idea of cross-pollination is my argument that education should be acknowledged as a complex field of professional practice, where context is king. What is ‘best practice’ in one context and with one cohort might not work as well in other contexts or with a different cohort. As a teacher, you will need to use your own professional judgement when deciding how and when to adopt and adapt the ideas and examples presented in the book which aim to enhance your pedagogical repertoires. The mezes are on the table, it’s up to you to select appropriate combinations for your meal.

Conclusion

At the start of this chapter, I proposed this reflection exercise:

Activate your inner dialogue… How would you answer?

How would you define inclusive learning design?

What questions do you hope to answer by interacting with the book and this companion website?

My provisional, evolving definition is:

Inclusive learning design is design that considers the full range of human diversity with its complexity. It is designing learning environments, experiences, activities, tasks, assessment and feedback with students’ voice and choice at its heart, so that students can grow academically, culturally and socially.

Regarding the second question, now that I have told you a little more about my intentions for my book, I invite you to think about the ways in which you got ‘stuck’ in the past, regarding inclusivity, where things did not work out and you want to do it better next time. This guide can be your got-to resource for ideas and examples of inclusive pedagogies to inspire and support you make the needed changes. However, ultimately what you choose to do with the material presented will depend upon your own personal history, your students, your discipline and the contexts within which you teach.

I now invite you to turn your attention to the roots of the learning design tree by reading Section 1 (in the printed/ebook version) where I will discuss nine inclusivity values that are my educational drivers.

References

Agostinho, S., Bennett, S., Lockyer, L. and Harper, B. (2013). The Future of Learning Design. London: Routledge

Austen, L., Hodgson, R., Heaton, C., Pickering, N. and Dickinson, J. (2021). Access, retention, attainment and progression: an integrative review of demonstrable impact on student outcomes. AdvanceHE.

Barnett, R. (2000). University Knowledge in an Age of Supercomplexity. Higher Education. 40. 409-422. doi: 10.1023/A:1004159513741

Baume, D. and Scanlon, E. (2018). What the research says about how and why learning happens. In: R. Luckin, ed., Enhancing Learning and Teaching with Technology – What the Research Says, 1st ed. London: UCL IoE Press, pp.2-13.

BBC News (2021). Euros 2020: What all of us can learn from Gareth Southgate. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-57698821

Bornschlegl, M. and Cashman, D. (2019). Considering the role of the distance student experience in student satisfaction and retention. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 34(2), 139-155. doi: 10.1080/02680513.2018.1509695

Bozalek, V. (2022). Attuning to Difference for a Justice to Come. [webinar] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yPr25ENu00w.

Conole, G. (2013). Tools and resources to guide practice. In: Rethinking pedagogy for a digital age. B. Beetham and R. Sharpe (Eds). Abingdon, Routledge

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Dalziel, J., Conole, G., Wills, S., Walker, S., Bennett, S., Dobozy, E., Cameron, L., Badilescu-Buga, E. and Bower, M. (2016). The Larnaca Declaration on Learning Design. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2016(1): 7, pp. 1–24, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/jime.407

Dirksen, J. (2015). Design for How People Learn. San Francisco: New Riders.

Florian, L. and Black-Hawkins, K. (2011). Exploring inclusive pedagogy. British Educational Research Journal, 37(5), 813–828. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23077052

Goodyear, P. and Dimitriadis, Y. (2013). ‘In medias res’: reframing design for learning. Research in Learning Technology, 21. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v21i0.19909

Hailu, M., Mackey, J., Pan, J. and Arend, B. (2016). Turning good intentions into good teaching: Five common principles for culturally responsive pedagogy. In Promoting Intercultural Communication Competencies in Higher Education (pp. 20-53). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-1732-0.ch002

Healey, M., Matthews, K. and Cook-Sather, A. (2020). Writing about Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. Center for Engaged Learning Open-Access Books, Elon University, USA DOI:10.36284/celelon.oa3

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York City, NY: Routledge.

Hockings, C. (2010). Inclusive learning and teaching in higher education: a synthesis of research Evidencenet. Higher Education Academy

Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a Design Science: Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203125083

Lawrence, J. (2022). Inclusive Academic Practice as Pedagogic Competence. [Blog] The SEDA Blog. Available at: https://thesedablog.wordpress.com/2022/05/12/inclusive-academic-practice-as-pedagogic-competence/comment-page-1/#comment-7187

McArthur, J. (2021). The Inclusive University: A Critical Theory Perspective Using a Recognition‐Based Approach. Social Inclusion, [online] 9(3), pp.6-15. Available at: https://www.cogitatiopress.com/socialinclusion/article/view/4122/4122

QAA (2012). The UK Quality Code for Higher Education. Available at: https://www.qaa.ac.uk/docs/qaa/quality-code/quality-code-overview-2015.pdf?sfvrsn=d309f781_6

Readings, B. (1995). Dwelling in the Ruins. Oxford Literary Review, 17(1/2), 15–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43973733

Sembiring, M.G. (2015). Validating Student Satisfaction Related to Persistence, Academic Performance, Retention and Career Advancement within ODL Perspectives. Open Praxis. doi: 7. 10.5944/openpraxis.7.4.249.

Shulman, L.S. (2005). Signature Pedagogies in the Professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52–59. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027998

Smith, J.G. (2017). The Garden: An Organismic Metaphor for Distinguishing Diversity from Inclusion. Graziadio Business Review, 20(2), August 2017.

Stentiford, L. and Koutsouris, G. (2021). What are inclusive pedagogies in higher education? A systematic scoping review, Studies in Higher Education, 46:11, 2245-2261, doi: 10.1080/03075079.2020.1716322

Citation

Rossi, V. (2023) Inclusive Learning Design in Higher Education – A Practical Guide to Creating Equitable Learning Experiences. London: Routledge