I use my ‘roots to shoots’ approach to more inclusive learning design to lead workshops for practitioners and educational developers who want to (re-)design (or support the redesign of) learning experiences such as university modules or courses.

For an overview of the workshop, read a summary blogpost about the workshop that I offered at the University of London in January 2023, including a Padlet which visually captures the workshop outputs from the groups.

While the following case study is a first-hand account of the workshop’s impact on educational developers who participated in 2021 and used the ‘roots to shoots’ approach to redesign an extended learning design workshop they offer to Aga Khan University academics. The authors are two Associates of the Network of Teaching and Learning (TL_net ) with responsibilities across Aga Khan University: Edward Misava Ombajo (Nairobi, Kenya), Digital Teaching and Learning (DTL) and Kiran Qasim Ali (Karachi, Pakistan), Teaching and Learning (TL).

The ‘Re-Thinking Teaching’ Workshop of Aga Khan University through the ‘Roots to Shoots’ Inclusive Learning Design Lens.

The Aga Khan University, founded three decades ago, is a multi-site university with campuses in six countries (Pakistan, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, United Kingdom and Afghanistan) across three continents. There are 11 teaching sites offering undergraduate/graduate programmes in three major disciplines – medicine, nursing, and education. The university is committed to promoting excellence in teaching and enriching students’ learning. At AKU, the Network of Quality, Teaching and Learning (QTL_net) offers various programmes to support faculty in the areas of curriculum review, course design, teaching methodologies, teaching with technology, assessment, etc. These programmes are designed on the principles of adult learning (Lieb1991), active learning (Felder and Brent 2016), peer learning (Boud2001), and reflection on teaching/own practice (Sööt and Viskus 2015).

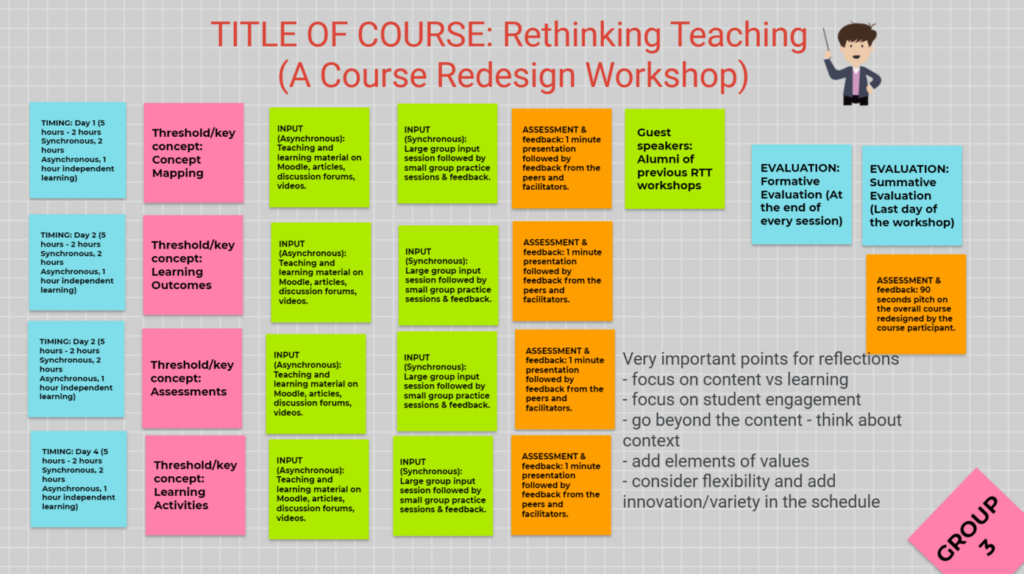

One of the QTL’s flagship programmes is the Rethinking Teaching (RTT)- A Course (Re)design Workshop, offered annually in Karachi and biennially in East Africa. The workshop aims to develop participants’ conceptual understanding of the course (re)design principles/processes and encourage them to apply them in (re)designing their own selected courses. This workshop is helpful to faculty who are either developing a new course (not a programme) or revising an existing one where student learning is the center of all teaching activities. It is also helpful for programmes that have recently undergone a cyclical QA programme review and/or programmes due to undergo self and peer assessment.

The RTT workshop is internationally recognized, peer-led and has been offered seven times at AKU. The workshop has been offered face-to-face five times from 2017-2019; however, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, we (re)designed the workshop for online delivery. In order to ensure that the online version of the workshop follows the principles of online learning design and is aligned with current best practices, we used the ‘Roots to Shoots’ model to redesign the workshop and adapt the workshop structure and facilitation to better suit digital environment and needs of the faculty member. Redesigning workshops based on evidence-based models ensures that we are directing our resources in the right direction and is designing practical, relevant, and realistic programs for faculty members. The redesigned RTT workshop was a 30-hour programme spread over six half days. The workshop was offered in June 2021, and twenty-four faculty members and academic support staff from different AKU entities in Pakistan, Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and the United Kingdom participated in various synchronous, asynchronous, and independent learning activities. This narrative highlights our experiences and reflections of using the ‘Roots to Shoots’ approach to (re)design and deliver the RTT workshop.

Overall, we found that the ‘Roots to Shoots’ approach was helpful in two significant ways. First, we found that the tree analogy provided a holistic approach to (re)design the workshop based on five fundamental principles of learning design: values, context, content, assessment and evaluation. Often, courses/workshops are designed and delivered in a manner where these five components are either developed separately or are looked at as segregated and unconnected pieces. The tree analogy helped us understand how these five components are connected, interdependent, and leading to one another. For example, while designing RTT, we realized that considering the essential elements of context (needs analysis, physical/digital space and community and support culture) provided us foundational information to effectively plan and deliver the input (i.e., content). Moreover, as we modelled this approach during our workshop, the participating faculty found it quite transformational as it changed the way faculty members viewed learning. They found the tree analogy an integrative approach as it served as connection points, bringing together various aspects of the course design that seemed disparate or unrelated for students’ learning.

Second, the idea of inculcating values while designing the workshop was relatively new learning for us. Integrating values into professional courses challenged faculty members to rethink what values we aim to integrate through our course. For example, while redesigning RTT, we primarily took care of integrating the values of inclusiveness, peer collaboration, co-creation of knowledge, and a non-judgmental approach to providing feedback (Higbee et Al 2008). These values were explicitly shared with participants on Day 1 of the workshop and were continuously demonstrated throughout the workshop activities.

The image below is a screenshot of the Jamboard (digital board by Google) which we used during the ‘Roots to Shoots’ workshop to redesign the RTT workshop for teachers:

Phase 1. Establishing Values and Principles of Learning

The starting point in the (re)designing the RTT workshop was establishing the teaching-learning values and principles. Setting up values and principles helped us lay a firm foundation of the nature of the teaching and learning process and the relationship we aimed to have between the facilitators and the participating faculty, which is crucial for the entire design process.

The three branches of the tree – the set up and engagement, the input and practice, and the outputs and feedback – constituted phases 2, 3 and 4 of the ‘roots to Shoots’ approach and were beneficial to the (re)design of the course from a holistic perspective. The section written below represents how each phase of the journey from roots to shoots helped in effectively redesigning the RTT workshop:

Phase 2. Establishing Context

The SDGs, especially goal number 4 on quality education and the university graduate attributes and program learning outcomes, formed the context of the redesigning process for this workshop. We conducted needs assessments with the faculty before the commencement of the workshop. The needs assessment helped us in three ways:

i. It provided us with the background of the participating faculty and the courses they planned to (re)design as part of the workshop.

ii. It provided us information regarding participants’ baseline knowledge about the course (re)design process.

iii. It laid out some of the needs and areas of concern for AKU faculty to tailor the workshop to suit their needs and concerns.

The needs assessment also allowed the team to revisit the workshop structure and space to ensure it is inclusive for all participants. Along with a needs assessment, we also conducted a brief orientation for participating faculty to discuss the outcomes and goals for the workshop.

Phase 3. Establishing Content

While rethinking the workshop’s content, we used and modelled the ‘threshold concepts’ (Land et Al 2018) approach. Identifying threshold concepts guided our course redesign process by helping us identify the essential learning outcomes to avoid ‘content overload’ (Sweller 1988) in the workshop. Also, for faculty, this approach was useful as it helped them avoid ’overstuffing’ their own courses.

During the workshop, participants were also encouraged to use this approach to redesign their courses. During the workshop, we observed that using the threshold concept approach helped faculty better organize their courses and provided a lens through which faculty members could keep student learning at the centre and helped them shift their focus away from content delivery to active, transformative learning. One of the faculty members highly appreciated the approach of using learning thresholds in (re)designing their courses and said:

‘Using [threshold concepts] is a great tool to help students connect with the major concepts of the course and enjoy learning. This approach has inspired me to learn new ways of teaching, assessing and evaluating the course’ [Faculty, Medical College, Pakistan].

While deciding the methodology of the course, we employed a flipped-classroom approach (Talbert 2017) to design and deliver the workshop content. We created a digital space on our Virtual Learning Environment (Moodle) for asynchronous activities and Zoom Web Conferencing Software for online synchronous activities. The workshop was divided into four (mini) modules starting from participants reconceptualizing their courses through the concept mapping (threshold concepts) approach, then moving into integrating the learning outcomes, assessment strategies and teaching methods to it. Each module began with asynchronous activities on Moodle, where participants develop their conceptual understanding of that particular theme through different activities assigned to them in advance. The asynchronous activities were followed by a synchronous session where participants were engaged in live discussions in large groups to extend and enrich their understanding of the module’s theme. After large group discussions, participants were divided into small groups where they worked on (re)designing their own courses and applied the principles learned in the large group. On the last day of the workshop, participants were expected to make a 10-minute presentation to present the process of redesigning their courses to their colleagues and facilitators, followed by peer feedback.

The flipped classroom approach was instrumental. It helped us organize our content and activities into synchronous, asynchronous and independent learning modes, thereby creating flexibility for participating faculty and facilitators and allowing them to interact with facilitators and other participants at different levels. Also, it prevented content overload during synchronous sessions and guided us to use synchronous time effectively for more higher-order thinking activities, such as discussions, reflection, peer feedback, etc. In addition, the flipped classroom approach created an atmosphere for self-directed learning due to which participants owned their learning and demonstrated their accountability towards their progress in the course.

Through large and small group discussions, peer-interaction, readings, and one-on-one and continuous peer feedback, the RTT workshop provided faculty with a facilitated opportunity to deeply reflect and rethink their course design strategy to help their students achieve significant learning experiences. In particular, the step-by-step approach of moving from threshold concepts to outcomes, assessment and strategies enabled faculty to view their courses from a more holistic perspective instead of considering the various course elements (threshold concepts, learning outcomes, teaching methods, and assessments strategies) as segregated pieces. One of the participants said:

‘Each activity in the workshop prepares you more. We were not that much aware of our courses as we are now. It is all because of RTT. Thank you for this awesome opportunity’ [Faculty, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Pakistan].

Each day participants were allowed to work in small multidisciplinary groups and share their course concept maps with colleagues for feedback and further improvement. This peer-led approach in the workshop created a safe, inclusive space for faculty members to learn from each other, explore new ideas and exchange feedback using a non-judgmental approach. Also, the small group discussions allowed faculty members to work with faculties from other disciplines to learn from their experiences, build understanding and explore avenues to stimulate their thought process about issues related to teaching and learning from all viewpoints.

‘The RTT course was an eye-opener for me; thinking of instructional strategies and assessment strategies and aligning them with learning outcomes was a eureka moment for me. I kept thinking and reflecting on my teaching and learning methods to see where I could make changes and improve. RTT sparked a change like a small wave, and hopefully, this will have a ripple effect and grow into one big giant wave of change in the teaching and learning process’ [Faculty, Medical College, Tanzania].

Phase 4. Establishing Assessment Measures

At the end of the workshop, all participants showcased their (re)designed courses through a 90-seconds pitch followed by constructive feedback from their peers and facilitators. During the 90-seconds pitch, each participant presented their (re)designed courses with their threshold concepts, the learning outcomes, assessment strategies and learning strategies. Both formative and summative evaluations were conducted during the workshop to gauge participants’ views on different aspects of the workshop and tailor the workshop based on participants’ needs and concerns. Notably, the formative evaluations conducted on a daily basis during the workshops regularly informed the team about participants’ needs.

We found the ‘Roots to Shoots’ approach beneficial as it provided us opportunities to consider and make choices regarding different aspects of the course redesign process concerning the comfort level of the facilitators, available tools at the institution, learning outcomes of the course, availability of necessary software or hardware to the students, and, most importantly, the particular goals of the course redesign.

We strongly believe that successful course (re)design is an iterative and ongoing process (Phase 5 of the ‘Roots to Shoots’ approach). It often follows the cyclical structure for continuous improvement as part of a sustainable process that enhances student learning experiences.

______________

References

Boud, D. (2001). Making the move to peer learning. In Boud, D., Cohen, R. and Sampson, J. (Eds.) Peer Learning in Higher Education: Learning from and with each other. London: Kogan Page.

Land, R., Cousin, G., Meyer, J. and Davies, P. (2018). ‘Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (3): implications for course design and evaluation’. In: C. Rust, ed., Improving student learning: diversity and inclusivity. [online] Oxford: OCSLD, pp.53–64. Available at: https://www.ee.ucl.ac.uk/~mflanaga/ISL04- pp53-64-Land-et-al.pdf Also available as video conference at: https://vimeo.com/91920616

Lieb, S. ( 1991). Principles of adult learning. Retrieved August 5th ,2021, from http://honolulu.hawaii.edu/intranet/committees/FacDevCom/guidebk/teachtip/adults-2.htm

Sööt, A. and Viskus, E. (2015). Reflection on teaching: A way to learn from practice. Procedia, 191, 1941- 1946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.591

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12, 257–285 https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1202_4

Talbert, R. (2017) Flipped learning : a guide for higher education faculty. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus Publishing.

For an overview of the workshop, read a summary blogpost about the workshop that I offered at the University of London in January 2023, including a Padlet which visually captures the workshop outputs from the groups.